Twelve Satyr Shakespeare is one of the newest theatre companies in town (they seem to be popping up overnight), a venture started by recent Shakespeare at Winedale alums Leo Weiser and Andrew Wissman. For their first performance, Twelve Satyr staged The Winter’s Tale – an intrepid choice, as it’s not one of the Bard’s more popular works due to its refusal to fit neatly into “tragedy” or “comedy” boxes. But even if you’re not familiar with the plot, you may recognize a specific stage direction found in its third act: Exit, pursued by a bear.

Winter’s Tale was directed by Weiser and Wissman, but they were both also performers in it. Weiser played Leontes, the deeply flawed and jealous king of Sicilia, who within the first scene of the play becomes convinced that his wife Hermione (Samantha Plumb) has been unfaithful to him with his maybe-brother/the King of Bohemia, Polixenes (Oliver Holder) and that the child Hermione is pregnant with is not his, leading Leontes to imprison his wife, exile the infant, and live in despair. Well, until the infant grows up, falls in love with the prince of Bohemia, coincidentally finds her way back to Sicilia 16 years later, a statue of Hermione comes to life, and everyone gets a happy ending.

(It is a weird play.)

Weiser seems to follow an old-school, As-Dramatic-As-Possible theory of Shakespearean performance. He elongated vowels and delivered lines in an odd, melodramatic cadence; almost a parody of a mid-century sensibility. Creative, certainly, but a bit too much delivery and not much character. Conversations with Leontes came to a crawl when it was Weiser’s turn to speak. The rest of the cast gave much more natural performances, to varying success. Wissman, for example, was easygoing and hilarious paired with Mike Dellens as the Clown and Shepherd, respectively. Their first comic scene just before intermission was a welcome relief after the slogging first act. Samantha Plumb was quite good as Hermione, but unfortunately staging didn’t help her much. In the emotional, heartbreaking, very long monologue where she pleads for her life, Plumb was left with nothing to do except circle the stage over and over as the monologue went on and on. Many of the cast seemed unfamiliar with Shakespeare’s language and it was unclear if they truly knew what they were saying; thankfully, though, most were loud and clear in Trinity’s black box. The only actor I had difficulty understanding was Oliver Holder as Polixenes.

Many of the other aspects of the play lacked polish. The cut of the script is odd; they left in exceedingly long monologues but cut a scene where Polixenes and Camillo (Derek Byzinzki) don disguises to spy on Polixenes’ son Prince Florizell (William Bain, dressed like Aladdin in a vest and no shirt). They were still there to rip off their disguises later, so why skip the scene explaining why they put them on in the first place? In another scene, Florizell asks to switch clothes with rough con man Autolycus (Austin Little), in order to sneak away from home. In the script, Autolycus is then mistaken for a nobleman because he is wearing Florizell’s clothes – but in Twelve Satyr’s staging, the two didn’t switch clothes – Autolycus just gave Florizell his outer coat – so this mistaken-for-a-noble scene made little sense.

Besides the script (I did say it’s a weird one!), other choices belied Weiser and Wissman’s inexperience. The lighting for much of the show was a dim orange wash, which was unusual choice, though I suppose not an offensive one. But then midway through the first act, Leontes entered and began a monologue in total darkness. I was convinced the light board operator had missed a cue and glanced their way, but several moments later another character entered with a lit lantern. Clearly, the darkness was intentional. This “nighttime” trick was repeated twice more with lanterns and candles, and it worked only once – in the last scene of the play, it adds some believability to the “living statue” of Hermione. Costumes were another aspect that sometimes made sense and sometimes didn’t. Everyone in Sicilia was dressed in all white, head to toe, reflecting Leontes’ cold, immovable fury. In Bohemia, all wore costumes a bit reminiscent of Hobbits, perfect for a sheep-shearing festival: earth tones, waistcoats, tiered skirts. Except, for some reason, Mamillius (Samwise Aiden Mauk) and a Lord (Christian Huey) wore the same “Bohemia” costumes for the entire show, whether in Sicilia or Bohemia. Did Mauk and Huey’s white costumes not arrive in time?

Directing, acting, designing, finding performance and rehearsal space, raising money, wrangling an audience – that’s a lot to do, especially for one’s first production. Wissman and Weiser’s directors’ note says that they decided to put on a show because. . .”Why not?” which is a perfectly good reason to do any art. (And as I’ve opined before, community theater might be the most important art of them all.) That said, theater is a lot of work, Shakespeare is a beast of its own, and The Winter’s Tale isn’t an easy show. That they got it on stage should be congratulated. In all, though, Twelve Satyr bit off a whole lot for their premier production, and it was likely more than they could chew.

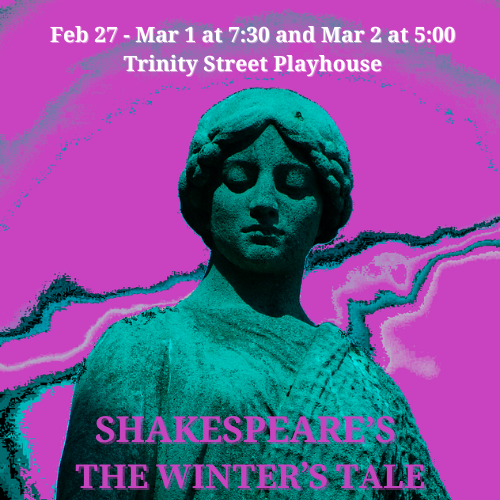

The Winter’s Tale ran at the Trinity Street Playhouse from February 27 – March 2, 2025. For more information, view the program here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.